How a Canadian Dollar Store Became One of the World’s Most Profitable Retailers

Retail chains aren’t known for particularly high profit margins, but Dollarama—where many items sell for just C$1—is the surprising exception.

Key Takeaways

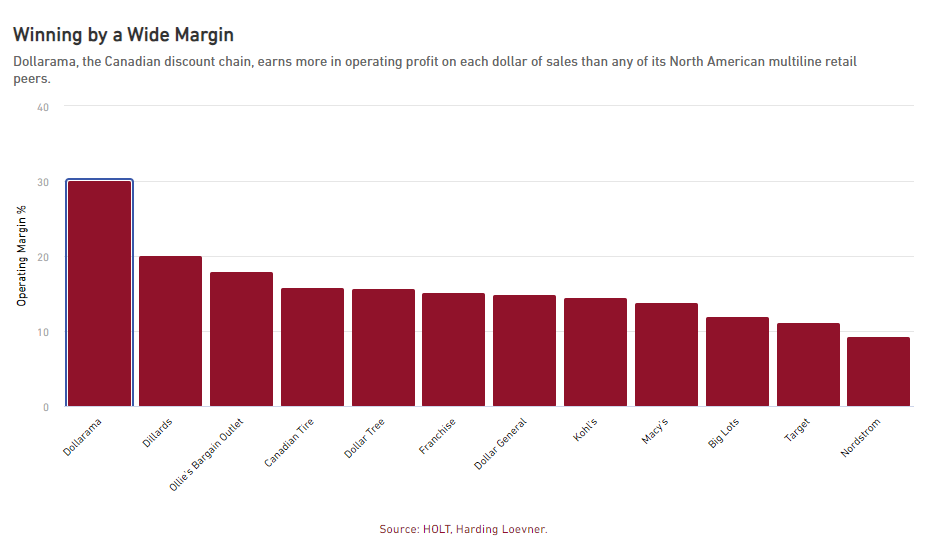

- Dollarama earns a higher profit margin than any other large department store or discount chain in North America, including Target and Costco.

- Canadian retailers have an advantage over US discount stores that compete in more saturated markets and are encouraged to stock lower-margin basic foods.

- Because the company is especially skilled at private-label merchandise that closely resembles pricier brands, there are now social media accounts dedicated to finding the best Dollarama dupes.

The world’s largest retailers are lucky if they earn a few pennies on each dollar of sales. At Costco, a US$230 billion chain, the adjusted operating profit margin is just 4.5%—less than a nickel per dollar—and that’s considered good. Retail is an intensely competitive business that operates with costly levels of inventory, labor, and physical space.

But there is one company that seems to defy standard retail math. For the past half-dozen years, Dollarama, a dollar-store chain in Canada valued at C$22 billion (US$16 billion), has enjoyed operating margins of about 30%. This means Dollarama is not only the most profitable company in its North American peer group, but it also earns a higher margin than almost any other retailer in the world with at least US$1 billion in market capitalization. And of the 50 largest consumer-discretionary companies globally—a broader bucket that includes US giants such as Marriott and McDonald’s—Dollarama’s operating margin ranks ninth, just behind the luxury brand Christian Dior.

“I haven’t come across many businesses in store-based retail with that kind of margin,” said Samuel Hosseini, a consumer analyst for Harding Loevner. “It’s unusually attractive.”

Dollarama has four key strengths that underpin its success. None is a sufficient explanation on its own for the uniquely high profits, but together these four factors have enabled a Canadian discounter to outmaneuver an entire industry.

1. It’s a dollar store

While it may seem counterintuitive, dollar stores tend to be among the most profitable segments of retailing. Dollar General, the largest dollar-store chain in the US, regularly posts operating margins of about 15%. Five Below, a US chain targeting teen shoppers with items priced below US$5, has generated operating margins in recent years as high as 23%.

Part of the reason is that dollar stores aren’t always as cheap as they seem. They predominantly cater to the cash-flow timing of lower-income consumers: while the US$20 bottle of laundry detergent at a supermarket might be a better deal on a per-laundry-load basis, that’s not relevant if you have only US$5 in your budget for detergent in a particular week. In the end, the total transaction size at the dollar store may be smaller, but so are the individual package sizes, which can disguise the per-unit markup. And because dollar stores are often situated closer to residential neighborhoods—unlike other big-box stores clustered in central shopping areas—they can charge a small premium for convenience, similar to 7-Eleven.

Dollar stores are also able to maintain a lower cost structure than other retailers because customers don’t expect first-rate ambience, service, or even to find every item on their lists. Since they carry a limited assortment, there’s less pressure to stock a particular brand or product. This leads to higher bargaining power with suppliers. For example, a dollar store might sell only Coca-Cola, not Pepsi, or only the basic line of Colgate toothpaste rather than the whitening version; consumers expect Target and Walmart to have a broader offering. “The customers understand the deal,” Hosseini said. “The deal is, ‘You come into our store, we’ll sell you cheap stuff.’”

Economic trends over the last decade and in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic have further fueled growth for dollar chains. Inflation in food, fuel, and rent prices has led shoppers to seek greater savings, and with an aging population and shrinking households, individuals want alternatives to family-sized products. Meanwhile, as e-commerce upends much of the retail world, it has failed to make the same inroads with dollar-store shoppers uninterested in buying in bulk or paying for a shipping membership. As other brick-and-mortar retailers collapsed or downsized in the face of digital competition, dollar chains proliferated. In 2021, nearly half of all new store locations in the US planned by large retail chains were either a Dollar General, Dollar Tree, or Family Dollar (which was acquired by Dollar Tree in 2015).

2. It’s a Canadian dollar store

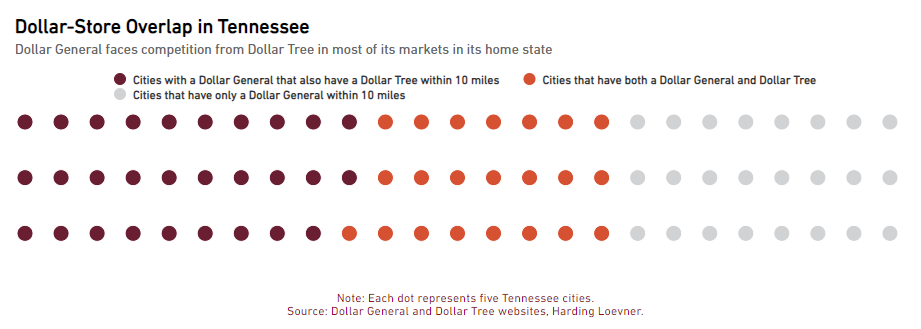

As dollar stores have spread across the US, the two leading chains, Dollar General and Dollar Tree, are fighting for customers in the same markets. For example, in Dollar General’s home state of Tennessee, two-thirds of its stores are within 10 miles of a Dollar Tree and about a third are in the same city—in some cases walking distance from each other. In Dollar Tree’s home state of Virginia, three-quarters of its stores are in the same city as a Dollar General, and nearly all its locations are within 10 miles of its rival.

Dollarama doesn’t face those same competitive pressures. Its 50% market share among general discount stores in Canada is more than twice what Dollar General and Dollar Tree together have in the US. And Dollarama’s C$4.5 billion in annual revenue exceeds that of its next ten largest local competitors combined.

The company also has considerably more room to expand because Canada still has relatively few dollar stores. Within the more densely populated areas hugging the southern border, there is one dollar store for every 20,000 Canadians—half the penetration level of the US.

“Dollarama is a great business, in large part because of its dominant position in Canada,” Hosseini said. “It’s got a good niche and an advantage in that niche.”

Even though Canada shares many similarities with the US, the country is known to have an affinity for local brands that are attuned to Canadian culture and consumer preferences. This helps insulate Dollarama’s business from US companies seeking to expand up north. And while the differences are subtle, they can be meaningful for retail strategies. Kantar, a marketing consultancy, found in a 2020 survey that Canadian consumers were more likely than American consumers to describe their country as inclusive, consider self-reliance and fairness as extremely important core values, and consider mental health the most important aspect of wellbeing; they were less likely than Americans to value convenience, hold firm religious beliefs, or aspire to home ownership. E-commerce also accounts for a smaller proportion of total retail sales in Canada than in the US, according to Emarketer, a media and marketing research firm.

There is another advantage to being in Canada. While Dollarama’s US counterparts stock their fair share of discretionary bric-a-brac, a large portion of their inventories skew toward staples, especially products eligible for the US Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps. With SNAP, recipients receive benefits through a payment card for use at participating retailers, which must meet certain inventory requirements for basic foods. In Canada, financial assistance is provided through supplemental income programs that don’t directly involve retailers. This allows Dollarama to stock a higher proportion of discretionary items, which earn higher margins, and a mix of products that appeals to a wider cross-section of the population.

3. It’s a treasure hunt

Most dollar stores sell plenty of items for more than a dollar. In Canada, Dollarama was among the first companies to aggressively pursue a multi-price strategy, which was necessary to counter inflation and widen margins. The approach wasn’t without hiccups, though. When Dollarama raised the price on some items to C$4 in 2016, customers rebelled and took to chat rooms to complain that the chain had become overpriced. Foot traffic declined, and same-store sales growth shrank.

Around this time, Neil Rossy, the great-grandson of Dollarama’s founder, became the company’s CEO. One of his first moves was to stock a larger selection of true dollar items, returning to the retailer’s roots. Today, Dollarama’s mix of C$1 staples and more splurge-worthy discretionary purchases—such as C$3 faux diamond tealight candle holders and C$4 knock-off Beats headphones—give the store a treasure-hunt feel that not only appeals to a broader set of incomes but also makes the chain enticing to social media users searching for unique deals. This has spurred an entire genre of “Dollarama finds” Instagram Reels and YouTube vlogs.

“These are discretionary purchases, but they are items that people are going to need or use,” Hosseini said. “They are affordable luxuries, which are good for Dollarama’s margins.”

4. It is highly skilled at private-label merchandise

Part of the treasure-hunt experience is Dollarama’s impressive array of dupes. Many retailers have their own generic labels that imitate known brands, but the private-label merchandise available at Dollarama is a cut above the usual pickings. In 1993, the company began developing relationships with overseas suppliers in countries such as China and stepped up those efforts in the early 2000s by expanding its direct-sourcing program in Turkey, Vietnam, and other hubs. These relationships helped Dollarama make more precise copies of popular products by replicating the very essence of what made the items appealing or recognizable to customers. For example, the retailer developed its own tiny plastic blocks indistinguishable from Legos that fit interchangeably with the authentic kind and bottles of “Spa Soap” that easily could be mistaken for Soft Soap.

Dollarama’s Studio stationery and Plastico storage containers are also a testament to its sharp eye for consumer trends and skill at creating brand confusion. The look and feel of these product lines can fool customers into thinking they are national brands like Bic and Rubbermaid rather than items exclusive to the discounter.

It’s this combination of being a uniquely Canadian dollar store and helping shoppers feel like they’ve scored a great deal that has made Dollarama’s margins the envy of the industry.

“The fallacy is that you’ve got to do something innovative to be incredibly profitable,” Hosseini said. “In retail I’ve found that’s not necessarily the case.”

Dollarama’s leadership team “has been smart,” he said. “When something worked, they kept going at it.”